John Miller is the award-winning author of three novels of literary fiction: Wild and Beautiful is the Night (Cormorant, 2018); A Sharp Intake of Breath (Dundurn, 2007), which won the 2008 Beatrice and Martin Fischer Award in Fiction; and The Featherbed (Dundurn, 2002).

A delicate question: How far will writers go for our craft – and at what cost?

How much, John Miller asks, should we or can we give those people in return for using pieces of their story? How far will writers go for our craft, and at what cost?

Originally published in The Globe and Mail on January 5, 2019. Globe subscribers can view the original essay here.

In December, 2007, I received an e-mail. “I relapsed and have found myself in a state of ugliness again.” My friend and former colleague Kim had been sleeping in crack houses for two months but had found a place to move into, and needed to come up with $400 to add to the $800 she’d already put down for rent. “I am emailing everyone I know for help. I feel so embarrassed but am desperate right now. So sorry for letting you down, John.” She asked if I’d call her.

A state of ugliness, to quote Kim, took hold of me as I wrestled with what I was about to do.

The next evening, I called Kim with a proposal: I wouldn’t gift or lend her the money, but I would contract with her instead, and my payment would be $400, the amount she needed. The job – to grant me two final interviews – would complete a process we’d started two years before, when Kim had been off of drugs for many years. Those interviews, the first of them given for free, were to be background information for Wild and Beautiful is the Night, my third novel, which, 11 years later, has made its way onto bookshelves.

Kim accepted my proposal and after we hung up, I considered how my chosen course of action touched on questions that writers ask each time we interview a research subject. How much should we or can we give those people in return for using pieces of their story? How far will we go for our craft and at what cost? Do the benefits to us and, later, our readers, justify the emotional toll such exploitation might take? Sometimes, there’s no exploitation, no harm and, therefore, no dilemma. Other times, as in my situation, it isn’t so clear.

Kim and I met in 2003, when for more than a year I filled in as executive director at the Toronto People with AIDS Foundation. She was the organization’s speakers’ bureau co-ordinator, a job that required her to dig into her past to speak publicly about her former crack-cocaine use and her experiences as a sex worker, an occupation she’d left years before; about the joys and struggles of motherhood; and about being a woman and a lesbian living with HIV.

Her primarily middle-class audiences related to Kim, in part because of her own middle-class background. She was lauded as an engaging speaker with a certain gift for holding a room in her thrall. I began to wonder if a fictional character similar to Kim might make a useful protagonist, one who might be a window into the complex issues faced by sex workers and people who use drugs.

Once I was no longer her boss, I asked if I could interview her in aid of a new novel I was considering. At first, she hesitated, but only because she’d been thinking of writing her memoirs. I encouraged her to do so and assured her that any novel I wrote would borrow details of her life to lend authenticity to more than one fictional character, but none of those characters would be a thinly veiled Kim. With that reassurance, she enthusiastically agreed. Kim wasn’t afraid of identifying information; but she cared who told her story and how it was told. She was no victim. She was proudly resilient and wanted that to be known.

In 2005, she and I met a couple of times and I asked her for specifics and anecdotes, for what it felt like then, as opposed to when she was in recovery. Those first interviews were reflections on a past she thought she’d left behind. At that point, the benefits to Kim seemed clear: She liked being seen as an expert; it made her feel good to help and she seemed pleased when I mentioned she’d be named in the novel’s acknowledgments. Since my writing income is paltry, I didn’t offer to pay her, then. Nor did I pay any of the other people I interviewed for my novel, including other drug users and sex workers. Most novelists don’t.

A few months later, Kim quit her secure job to start a small business. Although she was now too busy to meet for the rest of our interviews, Kim was genuinely excited to have a continuing part in my writing project. I was grateful whenever she brought it up; I was eager to dive into my story, but I still had research to do. I hoped, once things settled down, we’d be able to meet at length again.

Sadly, her business didn’t succeed, one thing led to another and, with the stressors piling up, she relapsed. At that point, someone called Children’s Aid and her son was removed from her care and sent to live with her ex-partner. Throughout this period, Kim and I sporadically kept in touch by e-mail and sometimes by phone. She raised the scheduling of our two final interviews, again, without my prompting, but understandably with her renewed challenges, as she went from relapse, to detox and treatment, to relapse and again into that all-consuming period of early recovery, those interviews were postponed several times.

Then, in December, 2007, came her e-mail asking for rent money. I wondered, was she taking advantage of our friendship and moreover, would I be establishing myself as an easy mark? Would my financial support be used for drug money? But I also wanted her to be housed. I was ashamed to be thinking in such a judgmental and self-protective way, and my next thought was how humiliating it must have been to make the request.

I laid out my possible courses of action, the three real choices I had: to say no, to give Kim the money without conditions or to pay her for her time. I weighed the good that might come of each, and the harm. There was no option that would cause no harm. I grappled with the competing sets of principles, laid them out in front of me, disheartened that so many were in conflict with one another. I tried to put myself in Kim’s shoes, even though I understand the limits to empathy when two people are in such different places.

I had to believe it was more ethical to help Kim, if I could, without subjecting her to that state of powerlessness, that feeling that erodes at our self-worth, when we can’t help ourselves. I didn’t want to be her saviour, nor for her to see me as one, as some parental figure who expected his gift to be used in the proper way. How condescending, how foul that would make me – to her and to myself. I considered that giving her cash without conditions might be taken a different way, that it might be accepted as a show of non-judgmental support, if I framed it right. I was her friend and that’s what friends are supposed to do: help one another without judgment. But she’d asked for that help and her need was so, so great. Would paying her for her expertise leave her feeling better and less like a charity case? Probably, although not by much, and there was no denying that this option benefited me the most; I very much wanted those interviews. I braced myself for her judgment.

On an icy December afternoon, I arrived early to a drafty coffee shop with fogged-up windows. Waiting for her, I contemplated my decision again, and the ugliness of its possible repercussions blew through me with each gust coming through the opening and closing door. Kim arrived on time. Weariness weighed her eyelids down. Her skin was grey. I probably didn’t look much better myself.

Our table was too close to the other patrons and my coffee was appropriately bitter. I selfconsciously gave her an envelope, which contained all of the cash for both interviews, and said it was hers for merely showing up. I hoped she’d stay, I said. I hoped she’d come back a second time, but if she felt it was too difficult, I’d understand. “Also, if my questions are too much, too intrusive,” I added, “you don’t have to answer. You can leave.”

Then, unable to meet her eye, I said, “I know I’m making you sing for your supper. Am I like one of your old tricks, minus the sex?” I started to cry and so did she. We held each other tightly in an embarrassingly long hug. When we sat again, she sidestepped my question, but she was exceptionally kind. “This novel’s going to be amazing,” she said. “I’m so happy to be able to help.” She squeezed my arm.

I marvelled at her generosity, at her humanity. At how, despite everything, she cared about soothing my self-reproach. She stayed, and the next week, true to her word, she showed up for the second interview.

Our conversations during those two December meetings were excruciating in their intimacy and in their honesty. Kim described her in-the-moment life without censorship or self-pity. Instead of reflecting back on a distant past, she described how she felt then and there. What it had been like for her that morning, as pains shot down her arms, and how it felt to sit in front of me, coming down from her high. “I’m beyond exhausted,” she said. She described what it had been like two hours earlier, as the drug she’d injected had taken hold. The oscillating optimism and hopelessness. She was breathtakingly self-aware and spoke with a heartbreaking blend of self-deprecating humour and sadness.

We hugged goodbye after that second interview, cried again, promised to keep in touch, and we did, a couple of times. Kim never again asked me for money.

A year and a half later, she died from an overdose. She never got the chance to write her story, in her own words.

It took me 10 years to finish the novel that began with those conversations. I scrapped a first manuscript, a very different story that took five years to write but failed mostly because I’d been too scared to mine the emotional honesty that was Kim’s true gift. I suppose I was too ashamed of how I’d come by it.

Ultimately, I started over, told myself that I owed it to her to see it through. The novel that has made its way to publication is deeper and rawer. Kim’s fighting spirit, humour, kindness and integrity have found their way into both of its protagonists. Still, I’m haunted by those last encounters. Elizabeth Epstein and Anne Hamrick, nursing professors and ethicists at the University of Virginia, describe what I’m feeling as moral residue, the feelings that linger after we’ve been involved in a morally ambiguous situation. To me, it’s the grimy film left behind when there was no great option, when you had to choose one, and the consequences have coated you and won’t wash away. I’m confident I made the best choice, but I could never bring myself to ask Kim if she agreed.

John Miller’s novel, Wild and Beautiful is the Night, was published in October by Cormorant Books.

Unforeseen hazards

With my friend Yves, there’s always an adventure. It shouldn’t have surprised me, then, when I joined his gay aerobics team on an excursion last March to a cabane à sucre outside of Montreal, that a year later, he would talk me into a costume party.

With my friend Yves, there’s always an adventure. It shouldn’t have surprised me, then, when I joined his gay aerobics team on an excursion last March to a cabane à sucre outside of Montreal, that a year later, he would talk me into a costume party.

So much about that last sentence amuses me. First, if you’re speaking of men, saying gay aerobics is mostly redundant. Secondly, has nobody mentioned to Montrealers that aerobics hasn’t been a thing since the early nineties? At least where I live, in Toronto, it hasn’t. Have Montrealers been aerobicizing all this time, or, like the trend-setters they often are, are they at the forefront of a neon spandex revival? Who knows. Also, they don’t just do aerobics, they’re a team! Finally, just the idea of dozens of gay aerobic dancers swarming a maple sugar shack, well, who would say no to such an invitation? Continue reading

Eluding (fake) rebel gunfire on Yew Tree Farm

International work has sporadically taken me to areas where poverty and politics—and sometimes conflict or terrorism—keep safety and security top of mind. I am not an inexperienced global traveller; my first real experience in the global south was on Canada World Youth in 1985, several months spent in a rural village in the Democratic Republic of Congo, back when it was called Zaire and under Mobutu’s military dictatorship. Since then I’ve backpacked in South America and Asia, done a degree in international development, and for the last ten years, global work in HIV has sent me on over seventy trips spanning every continent. Continue reading

International work has sporadically taken me to areas where poverty and politics—and sometimes conflict or terrorism—keep safety and security top of mind. I am not an inexperienced global traveller; my first real experience in the global south was on Canada World Youth in 1985, several months spent in a rural village in the Democratic Republic of Congo, back when it was called Zaire and under Mobutu’s military dictatorship. Since then I’ve backpacked in South America and Asia, done a degree in international development, and for the last ten years, global work in HIV has sent me on over seventy trips spanning every continent. Continue reading

Demonstrating on a Sleepy Sunday in Lithuania

Listen to John reading this essay on CBC Radio 1’s The Sunday Edition, Nov.17 2013

Listen to John reading this essay on CBC Radio 1’s The Sunday Edition, Nov.17 2013

A demo I attended recently in the sleepy capital of Lithuania reminded me of my long and conflicted relationship with public protest. I know that some demonstrations have changed the course of history. But with a few notable exceptions, the protests I’ve attended have been less Tahrir or Taksim and more Toronto. Less Tiananmen and more… just Tiresome.

I started protesting young, tagging along with my mother to abortion rights rallies, peace marches, gatherings to decry violence against women. These were mostly in Canada, the land of small demos and vast spaces, the vast spaces making small demos look even smaller. But I learned early on that, in a functioning democracy, expressing public anger at injustice is important- alongside political organizing and the occasional snappy letter to the editor. Continue reading

What happens to you when you ask a thousand HIV-affected children how they feel?

A meeting I attended in December, in Khayelitsha, one of Cape Town’s poorest townships, opened my eyes to the human cost of the social science research that fuels good policy—the cost to the people who collect the data.

A meeting I attended in December, in Khayelitsha, one of Cape Town’s poorest townships, opened my eyes to the human cost of the social science research that fuels good policy—the cost to the people who collect the data.

I spend a lot of time at conferences and meetings hearing about children and families living in the context of HIV and AIDS—about people who cope with the pandemic, sometimes succumb to its ravages, but mostly survive it and live on. I listen to presentations and read studies that report on statistics, studies that try to prove which inputs lead to which outcomes, and which inputs may lead to no outcome at all. These studies help policy wonks and philanthropists make better, more evidence-based decisions in the hopes that they’ll have positive and far-reaching impact. Continue reading

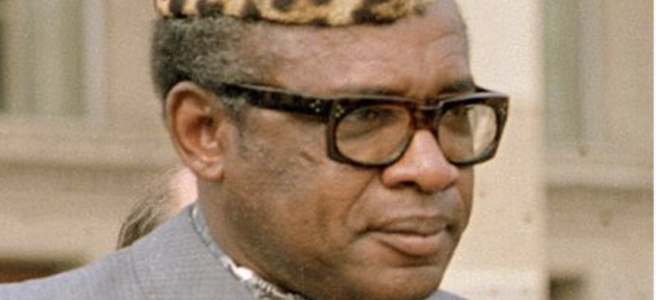

My day with Mobutu

Twenty-six years ago, on a beautiful marble balcony, I shook hands with Mobutu Sese Seko, the former dictator of what is now the Democratic Republic of Congo. I was reminded of that day last month while on a work trip to Kenya. In Nairobi, I happened upon a clothing store with a t-shirt bearing the face of Patrice Lumumba. Lumumba was the Congo’s first democratically elected president, but months into his mandate he was hounded from office, then hunted down and murdered by Mobutu following a CIA-backed coup. Mobutu ruled thirty-two years. His regime was brutal and repressive and while his resource-rich country withered, he amassed a fortune so large that he became the third richest man in the world. Continue reading

Twenty-six years ago, on a beautiful marble balcony, I shook hands with Mobutu Sese Seko, the former dictator of what is now the Democratic Republic of Congo. I was reminded of that day last month while on a work trip to Kenya. In Nairobi, I happened upon a clothing store with a t-shirt bearing the face of Patrice Lumumba. Lumumba was the Congo’s first democratically elected president, but months into his mandate he was hounded from office, then hunted down and murdered by Mobutu following a CIA-backed coup. Mobutu ruled thirty-two years. His regime was brutal and repressive and while his resource-rich country withered, he amassed a fortune so large that he became the third richest man in the world. Continue reading